30 May, 2025

Earlier this year, I embarked on a new project: listening to at least one album, front to back, each week.

I hadn’t intentionally listened to music in this way since the first lockdowns of the pandemic when I took to David Bowie’s discography on my daily walks (self-titled up to Let’s Dance). So over 16 years of music and months of isolation, I mapped out my entire neighbourhood on foot.

This year, in a daze of seemingly endless February—the doldrums of Canadian winter and the height of my yearly winter-induced mania—a part of me snapped in anger at the ennervating effects of the cold. I wanted a semblance of agency, of choosing something actively when everything else in my fugue life felt like it was happening to me. Taking control of what I was listening to seemed like a start.

♬⋆.˚.⋆♬

Nostalgia for my adolescence, a time when I was experiencing growing pains in tandem with the internet, partly fueled this project. I was deep in my daydreams of teenage reminiscence, specifically for the community my friends and I crafted around music. We'd browse through blogs, forums, music magazines and their websites; we'd find new music then go out into the world with it. We went to concerts. We attended comedy and art shows. We blogged about music on our respective Tumblrs. We regularly hung out at Amoeba Records and took our picks back to someone's house to listen together. We'd sit in one friend's backyard and literally just talk about music.

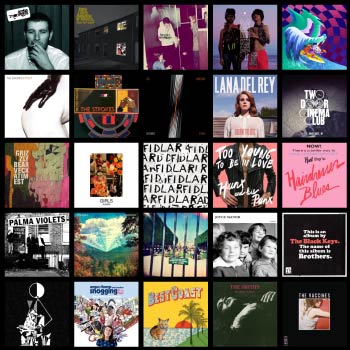

(Pictured above: indie sleaze but you're in middle school)

Now, not only has the practice of community in music listening virtually left my life, but so has much of the effort and dedication I used to invest in making sure I was contextualizing the art of real people. By contextualizing, I mean that I used to do deep dives on a band or artist's history. I'd read biographies, watch interviews and documentaries, learn about their influences for each album. It was these paratexts that helped paint a fuller picture of all the forces that begot a band, begot a record.

All this effort enhanced the music, humanized the artists, and deepened my connection to both.

♬⋆.˚.⋆♬

ADORNO & HORKHEIMER INTERLUDE!!

Another contributing factor to this project was rereading Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” earlier this year.

An alarmingly prescient term, the “culture industry” as Adorno and Horkheimer figure it is, in incredibly simplified terms, the guileless flattening of culture through the pursuit of capital.

The conspicuous unity of macrocosm and microcosm confronts human beings with a model of their culture: the false identity of universal and particular. All mass culture under monopoly is identical, and the contours of its skeleton, the conceptual armature fabricated by monopoly, are beginning to stand out. Those in charge no longer take much trouble to conceal the structure, the power of which increases the more bluntly its existence is admitted. Films and radio no longer need to present themselves as art. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce.1

And we've all been convinced to nod along. The "relentless unity"2 of the culture industry is shrouded by the false promise of innovation, a promise most of us do not fully believe in anymore. In reality, the "mechanically differentiated products are ultimately all the same."3 In other words, the options we're offered aren't even options at all; they're the same goods and services, except this one is in wet putty green while the other is in butter yellow.

Worst of all, we're made to feel empowered by our choices. Or rather, the illusion of it; an ersatz agency. In truth, there is no more thinking, not really. "For the consumer there is nothing left to classify, since the classification has already been preempted by the schematism of production."4 We are passive to the systems inescapable, and it's those systems that dictate the degree to which we are really able to choose anything at all.

We are tricked into pacification by the falsity of choice. Offering up a cheek, we're soothed enough to choose a fist for a punch.

However, it's important to note that this isn't an uninformed surrender by unthinking individuals, but a surrender numbed by cynicism and a uniquely ultramodern resignation. In this aporia, we can see elements of truth in what Adorno and Horkheimer declare in their essay: that the existing structure's power intensifies "the more bluntly its existence is admitted." I do believe many, especially young people, are aware of capitalism's tendrils crawling through the architecture of ultramodern life. It's just that the forces are so strong so as to effect a helplessness that we end up turning towards that very same cage to feel better, to cheat a freer-feeling life. It's knowing that the world is on fire and then getting a little treat to ease the existential pain.

♬⋆.˚.⋆♬

To bring it back to music, it's this:

It's learning that Spotify has entrenched in its royalty payouts program a new form of payola. In her book Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, Liz Pelly explains Spotify's "Discovery Mode" program, which "asks artists to accept lower royalty rates in exchange for algorithmic promotion."5 At a 30% lower rate, the cut is substantial and disproportionately advantages already big artists who have the backing of their major label. Those who can already afford to take a cut are the ones being pushed up Spotify's most popular playlists. This, in turn, pressures smaller indie artists to enroll in the program for fear of getting drowned out completely. It's pay-to-play, and some pay much more than others.6

Then, it’s doing your research to try and find which streaming platform pays its artist the most for their music. You find a few articles of dubious origin (no sources listed) stating differing numbers. You even find a royalties calculator (also no sources listed, though the disclaimer in the fine print specifies their figures to be USA-based). It’s realizing that, according to this calculator, you’d have to stream an artist on Tidal, apparently the highest paying service, nearly 4500 times to generate the equivalent of the price of a vinyl record. It’s having the privilege of soundtracking your life at the price of exploitation.

It's having a choice, which is to say, no choice at all. If it's not Spotify, it's Apple Music; if it's not Apple Music, it's Tidal, and so on. There's no believing these services in their declarations of so-called love for the art of music when they're paying their artists fractions of pennies on the impossible dollar while laying off hundreds of employees. They are business first, music dubiously next, all the while pushing their supposed ethos of "democratization" and "access". Such empty words spill from executives' mouths, hawked "as [the] ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce."7

♬⋆.˚.⋆♬

Remembering my old music listening practices in contrast to my current habits bummed me out. (Though, these practices were indelibly warmed by the shine of teenagehood: there was a surfeit of free time and little in the way of real responsibility.)

Over the last three-ish years, I've succumbed to the puppeteering of music streaming, specifically Spotify, its algorithms, and my passive listening. I still actively follow a handful of bands and artists I like, but apart form a very select few, I found myself mostly listening to isolated singles or whatever my daily mixes fed me. I was served up singles, listened to them obsessively for two weeks, then moved on. I ended up knowing little else about the artists outside of these lone tracks, let alone having the thought to listen to the full album from which the track was plucked.

Before I knew it, I began to rely on the nebulous Spotify algorithm to know me better than I knew myself. Boring!!!

♬⋆.˚.⋆♬

Next up:

- Methodology

- Friends' listening habits

- Analog

- Physical media

March-May 2025

-

Footnotes:

1. Adorno, Theodor W. and Max Horkheimer. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” In Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002, 95.

2. Ibid, 96.

3. Ibid, 97.

4. Ibid, 98.

5. Pelly, Liz. Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2025, 186.

6. And, it seems, people are beginning to notice.

7. Adorno & Horkheimer, 95.